Alan Lightman

On-Camera host and co-writer of searching

Alan Lightman is an American writer, physicist, and social entrepreneur. He is also the author of numerous books, both nonfiction and fiction, including Einstein’s Dreams, an international bestseller. His essays concern the intersection of science, philosophy, and theology and have been twice named by the New York Times as among the best dozen essays of the year, in any category. The Washington Post has called Lightman “the poet laureate of science writers.” Oprah described him as “A Renaissance man for a time such as this.”

In 2005, Lightman founded Harpswell, a nonprofit organization devoted to empowering young women leaders in Southeast Asia.

In SEARCHING, Alan investigates how key findings of modern science help us find our bearings in the cosmos. In the series and across this site, you’ll find Alan’s ruminations on science, philosophy, and more; and his reflections on being a first-time television host.

How It All Began

Written by Alan Lightman

In January of 2019, I received an email from someone named Geoff Haines-Stiles, saying that he had recently read my book Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine and was struck by some of its passages, and especially the one where I wrote that it was possible, in theory, to track the atoms in our bodies back to particular stars in the sky. He asked me to consider working with him on a public television program based in part on the book. Geoff also happened to mention that he had been a senior producer of the original Carl Sagan “Cosmos” series. I had admired that series for its grand scope, stunning cinematography, and appeal to the general public. I replied to Geoff that I would be interested as long as, in addition to hard science, the program could include the philosophical, ethical, and theological implications of science, as I had attempted to do in my book — including the aspects of human experience that cannot be captured with the reductionist methods of science. Geoff was game. As well as being a brilliant filmmaker, he is an all-round intellectual, broadly interested in the play of ideas. The following summer, he and his partner Erna Akuginow visited me on the little island in Maine described in the book. Although the visit was seemingly casual, I later realized that Geoff and Erna were probably looking me over to see if I was sufficiently articulate and photogenic in the flesh. They gave me the benefit of the doubt and proposed that we go ahead with the project, which eventually mushroomed into a 3-hour series. We were fortunate to receive funding from the Templeton Foundation and its then-director of public engagement, Christopher Levenick, who was enthusiastic about our project from the beginning. Making the series took three years and sent us to mountain tops in Switzerland, prehistoric caves in France, museums and graveyards in Italy, and farms in Cambodia, as well as to several locations in the United States. It was hard work, but it was thrilling.

It is my hope that “SEARCHING: Our Quest for Meaning in the Age of Science” will be entertaining, beautiful to watch, and thought-provoking.

Most importantly, I hope the series will help viewers better understand our place in this baffling cosmos we find ourselves in. And question what makes us human in a world increasingly shaped by science and technology.

Alan Lightman

On-camera host and co-writer, “SEARCHING: Our Quest for Meaning in the Age of Science”

Alan Lightman is an American writer, physicist, and social entrepreneur. He received his PhD in theoretical physics in 1974, working in the research group of Kip Thorne (2017 Nobel Prize, “Interstellar”). Since then, Lightman has done fundamental research on the astrophysics of black holes, astrophysical radiation processes, and stellar dynamics. He is a past chair of the High Energy Division of the American Astronomical Society and is an elected member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Lightman has served on the faculties of Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and was the first person at MIT to receive dual faculty appointments in science and in the humanities. He is currently professor of the practice of the humanities at MIT.

Lightman is also the author of numerous books, both nonfiction and fiction, including Einstein’s Dreams, an international bestseller, and the The Diagnosis, a finalist for the National Book Award in fiction. His essays concern the intersection of science, philosophy, and theology and have been twice named by the New York Times as among the best dozen essays of the year, in any category. His writing has appeared in the Atlantic, Granta, Harper’s, Nautilus, the New Yorker, the New York Review of Books, Salon, and many other publications. The Washington Post has called Lightman “the poet laureate of science writers,” Maria Popova, the curator of the widely read blog “The Marginalian” (formerly “Brainpickings”), has described Lightman as “one of the most poetic science writers of all time.” Edward Hall, chairman of the Harvard philosophy department, has said of Lightman “Deceptively brilliant, Lightman’s prose is so simple and graceful that it can be easy to miss the quiet, deep sophistication of his approach to the fraught topic of science and religion.” His book Searching for Stars on an Island in Maine (2018), an extended meditation on science and spirituality, was the basis for an essay on PBS Newshour. For his writing and his synthesis of science and the humanities, Lightman has received 6 honorary degrees, as well as other honors.

In 2005, Lightman founded Harpswell, a nonprofit organization devoted to empowering young women leaders in Southeast Asia, and he has served as chair of its board. For this work, he received the Gold Medal from the government of Cambodia.

Alan and Einstein's Ghost

Alan’s Personal Reminiscences

In October 2021, in the process of filming SEARCHING, I visited the house where Einstein lived from 1903 to 1905, on 49 Kramgasse Street in Bern, Switzerland. It was during 1905, working in near isolation, that he published his revolutionary theory of time and space, called special relativity. The young man was 26 years old at the time.

Although I wrote about Einstein and the city of Bern in great detail in my short novel Einstein’s Dreams (1993), I had never been there, much less to Einstein’s actual house. To write the book, I studied street maps of the old city of Bern, learned the location of such landmarks as the giant fountain and the clock tower, but I had never actually visited in person. I had wanted not to hamper my creative imagination with reality. When I was finished with the first draft of the manuscript, I sent it to some people who lived in Bern to correct any obvious geographical mistakes, such as the misplacement of small streets or the angle of viewing the Swiss Alps from certain cafes.

So it was a strange and moving experience to actually go to Bern. I had an odd sensation that I had been there before. The streets, the smells, the real clock tower, and Einstein’s house itself. The apartment where he lived with his wife Mileva and young son Hans Albert is on the second floor of a stone building, with many apartments and windows, each leading to a small balcony overlooking the street. You have to climb a steep and winding wooden stairway to get up to Einstein’s apartment. The sitting room, where I imagine Einstein worked with his pencil and paper, has a parquet floor, an oval table in the middle of the room, a wood chest on one wall, and a grandfather clock. It’s a small room. Today there are lots of museum-like photographs of Einstein on the wall, almost certainly not there in 1905.

Einstein is probably the most important physicist who has ever lived, aside from Isaac Newton. Every physics student learns his theories of relativity, gravity, his theory of light particles called photons, his work on “Brownian motion” and the size of atoms. Every physics student also learns something of his life. He was a loner. He was not such a good father and husband. But he was a scientific genius. I learned all of these things as a graduate student in physics. But after I wrote my little book Einstein’s Dreams, and later an essay about him for the New York Review of Books, I felt a deeper connection to him. I had tried to imagine him. I had tried to inhabit him, at least as much as another human being ever can. I had tried to understand his loneliness.

When I walked around the space where he lived and worked, I felt his ghost. Undoubtedly, some of the air that he breathed was still there in the room. Some of the molecules of his hand were still on the oval table. I placed my own hand on the table. I like to imagine that he could see me there, more than 65 years since he died, only a brief jump in time. Perhaps he could. As Einstein once wrote to the family of a recently deceased friend, “the distinction between past, present and future is only a stubbornly persistent illusion.”

The Brain and Consciousness

Following modern biology and neuroscience, we now believe that the activity of the brain takes place in neurons and in the interactions between them. We mostly understand how neurons work. A neuron consists of three parts: a cell body, which contains, among other things, the DNA of the cell; the dendrites, which are fibrous extensions of the cell that receive electrical impulses from other neurons; and the axons, which are long slender projections from the neuron that transmit electrical signals to other neurons. The manner in which electricity flows through the axons is understood as an exchange of electrically charged atoms through the axon membrane. Individual neurons put out “spikes” of electrical discharges, about 0.1 volt and lasting about 1 thousandth of a second. The manner in which messages are communicated from one neuron to the next is understood as a flow of certain chemicals, called neurotransmitters, across a tiny region between neurons called a synapse. All of these things have been observed, measured, and quantified.

There are about 100 billion neurons in the human brain. Each neuron connects to about 1000 other neurons, although the number varies from one part of the brain to another. Thus, there are about 100 trillion synapses in the brain. Human beings have the largest number of neurons of any known animal, except for the African elephant and some whales. Jellyfish have about 6,000 neurons; ants have about 250,000; mice about 71,000,000; ravens about 2,000,000,000; gorillas about 33,000,000,000; whales about 150,000,000,000; and elephants about 260,000,000,000.

Are whales and elephants “smarter” than us? Probably not, even though they are pretty smart. The most important measure of intelligence is likely not the absolute number of neurons, but the brain weight per body weight. Larger bodies require larger brains simply to manage all the nerve endings and internal functions, irrespective of intelligence. Thus, a more accurate measure of inter-animal intelligence is something neuroanatomists call the “encephalization quotient”: a comparison of the brain weight of a particular species against a standard brain weight of animals belonging to the same taxonomic group and with the same average overall body weight. By this measure, human beings are the “smartest” animals in our taxonomic group, with a brain weight 7.5 times the average mammal with our body weight.

Complex brain activity and consciousness is associated not only with the total number of neurons but also with the number of connections between neurons. As evidence: in the human brain, the cortex has fewer neurons than the cerebellum but many more connections between those neurons. From observing the association between behavioral manifestations of consciousness and damage to the cortex, neuroscientists have concluded that consciousness is much more associated with the cortex than with the cerebellum. The latter is responsible for much “unthinking” activity such as swallowing, and its neurons mostly act independently of each other. By contrast, neurons in the cortex have a great deal of interaction and feedback between themselves. A person can lose much or all of her cerebellum and still show all the signs of consciousness. Not so with the cortex.

Although modern scientists believe that consciousness and all brain activities emerge from the material neurons of the brain, there is as of yet no good understanding of how this comes about. Particularly the highest level of consciousness, the primal human experience we call “consciousness” – the first-person participation in the world; the awareness of self; the feeling of “I-ness;” the sense of being a separate entity in the world; the simultaneous reception and witnessing of visual images, sound, touch, memory, thought; the ability to conceive of the future and plan for that future – all of that is so unique, so hard to describe, so different from experiences with the world outside of our bodies that we may never be able to fully capture consciousness with brain research. We may never be able to show in a step-by-step manner how this highest level of consciousness emerges from the neurons and synapses of the material brain. That is not to say that such an emergence does not occur. We may be able to show that the feelings and attributes we call “consciousness” are generated by material structures in the brain without being able to fill in all the blanks. Similar examples of so-called “emergent phenomena” are illustrated in Part 3 of SEARCHING.

Alan’s latest book, The Transcendent Brain: Spirituality in the Age of Science (publication date March 14, 2023)

Element Production in Stars

In the first moments after the Big Bang, there were an equal number of protons and neutrons, the two subatomic particles that make up the nuclei of atoms. (Protons and neutrons themselves are composed of smaller particles called quarks.) These subatomic particles were whizzing around at great speed in the high heat of the early universe. The neutrons began to disintegrate into protons, electrons, and neutrinos, reducing their ratio to protons (which are relatively stable). At the same time, the protons and available neutrons began binding together to make the centers of helium atoms. Each helium nucleus has two protons and two neutrons. However, the universe was cooling and thinning out too rapidly for larger numbers of neutrons and protons to fuse together to make larger atomic nuclei like beryllium (4 protons and 5 neutrons) or carbon (6 protons and 6 neutrons). By the time the universe was about 20 minutes old, there were no unattached neutrons remaining. All the material of the universe was in the form of unattached protons (i.e. hydrogen) and helium nuclei, with about 12 protons for every helium nucleus.

The production of heavier elements, such as carbon and oxygen and nitrogen, would have to wait for the creation of stars, a hundred million years later. Stars can produce these heavier elements because the centers of stars sustain a high density of material (with the unattached protons and helium nuclei very close to each other), and that density remains constant, unlike the decreasing density of the early universe. Thus, at the centers of stars, hydrogen atoms and helium nuclei have plenty of time to find each other and join together.

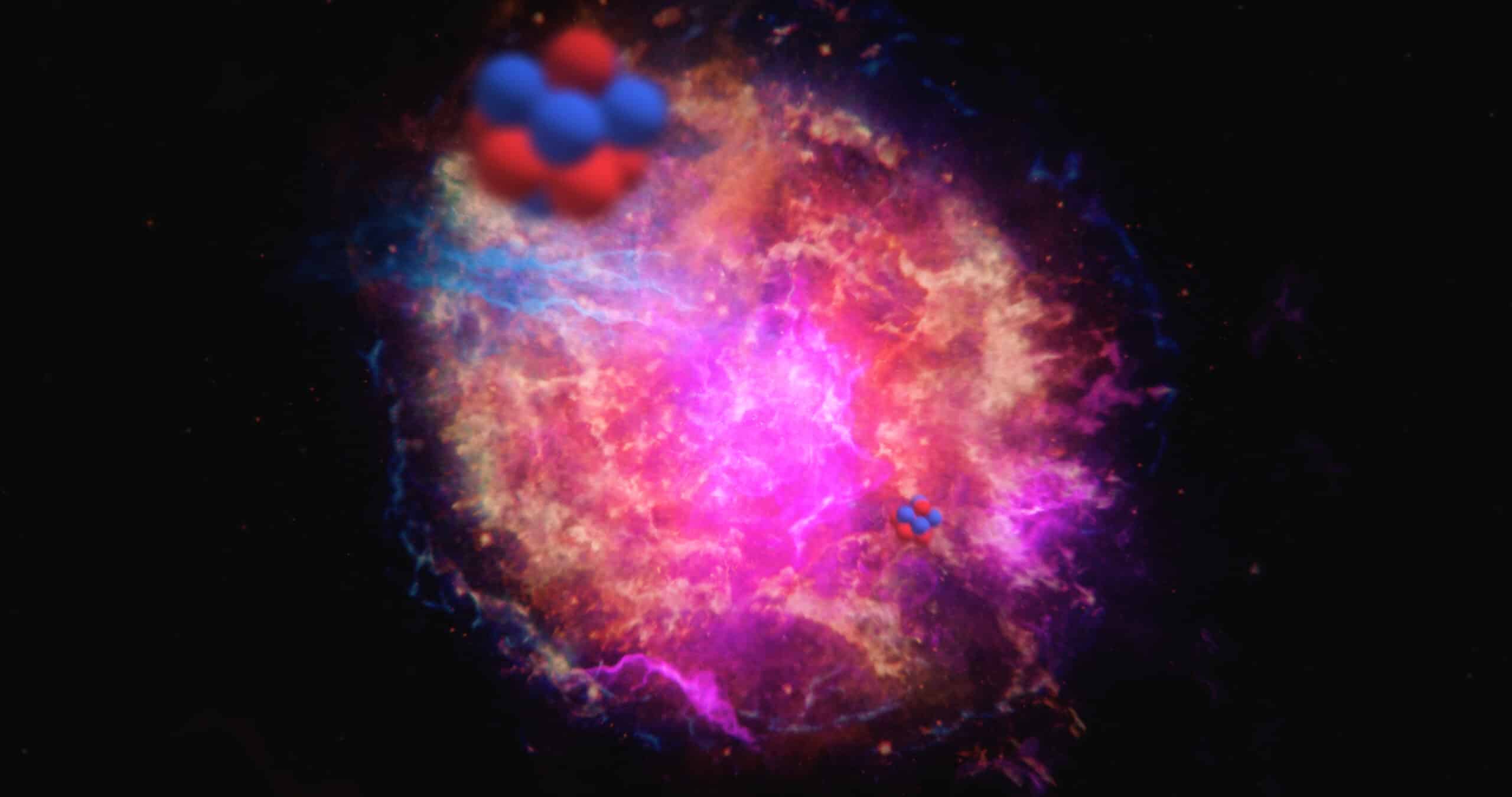

One of the principal processes by which the heavier elements are built up in stars involves the “triple alpha” process. (An alpha particle is the nucleus of a helium atom, most of which were created in the first few minutes since the Big Bang as discussed above.) In the triple alpha process, two helium nuclei fuse to produce beryllium-8 (4 protons and 4 neutrons). This nucleus is highly unstable and quickly decays back into smaller nuclei unless it is immediately struck by a third helium nucleus to form carbon, as shown in the diagram below:

After carbon is formed, a collision between a carbon nucleus and another helium nucleus can produce oxygen, which has 8 neutrons and 8 protons. This process of element building by the fusion of smaller atomic nuclei with larger ones continues to produce all the heavier elements – all in the hot and dense centers of stars.

Stars having a mass of about 10 times the mass of our Sun or larger end their life in a giant explosion, called a supernova. Such an explosion spews the guts of the star into space, including all the elements created in its center. These elements can then mix with the gas that forms solar systems.

A Short History of Harpswell

“Would you please build us a school?”

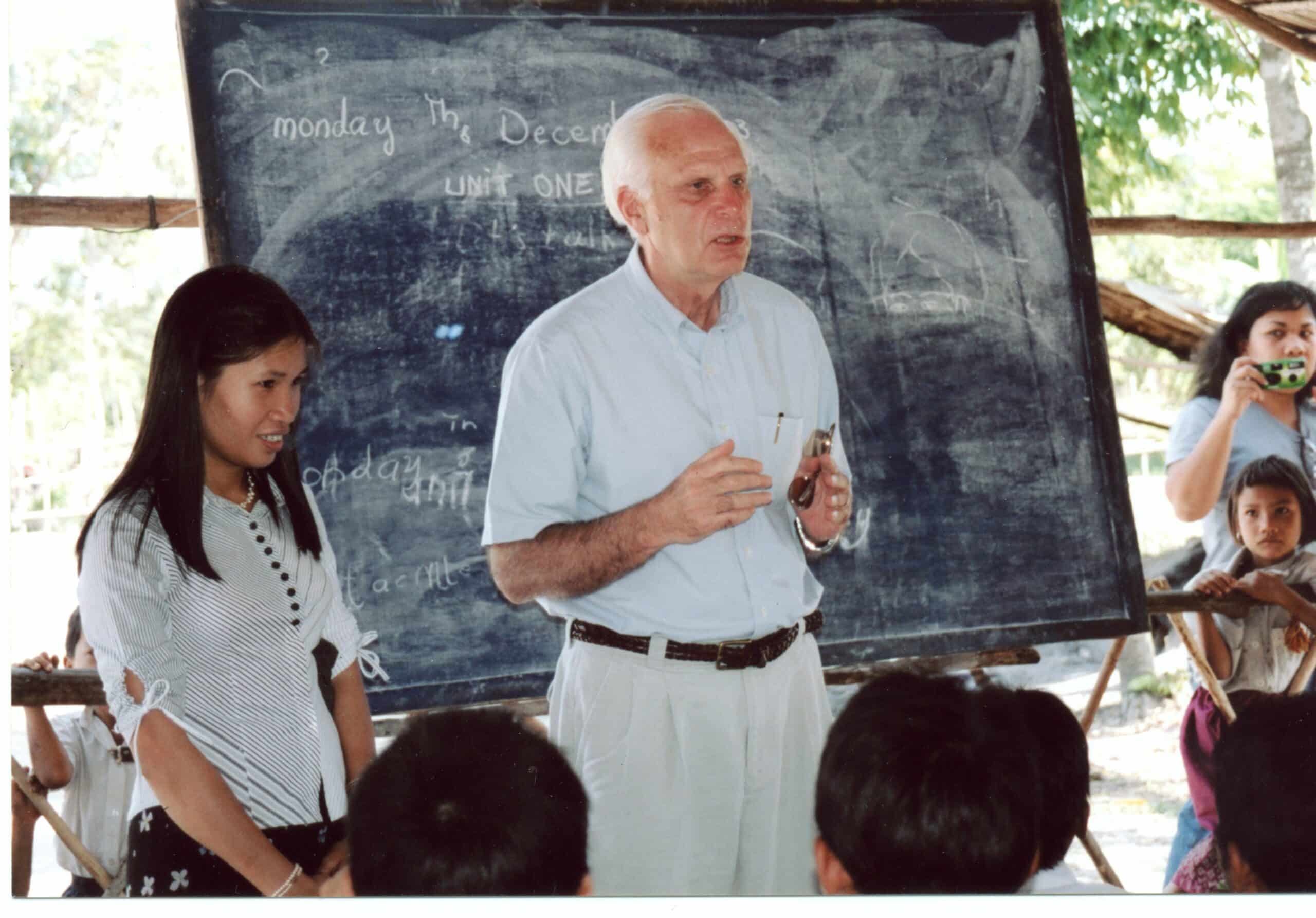

That was what the women said to me when I arrived at the small village of Tramung Chrum in rural Cambodia. The village had a temporary school, made of bamboo and palm leaves, simply a roof with no walls. In a strong wind, the matchstick construction blew down.

The women, holding their babies as they spoke to me, wanted a real school, made of mortar and brick. It was December 2003, my first trip to Southeast Asia.

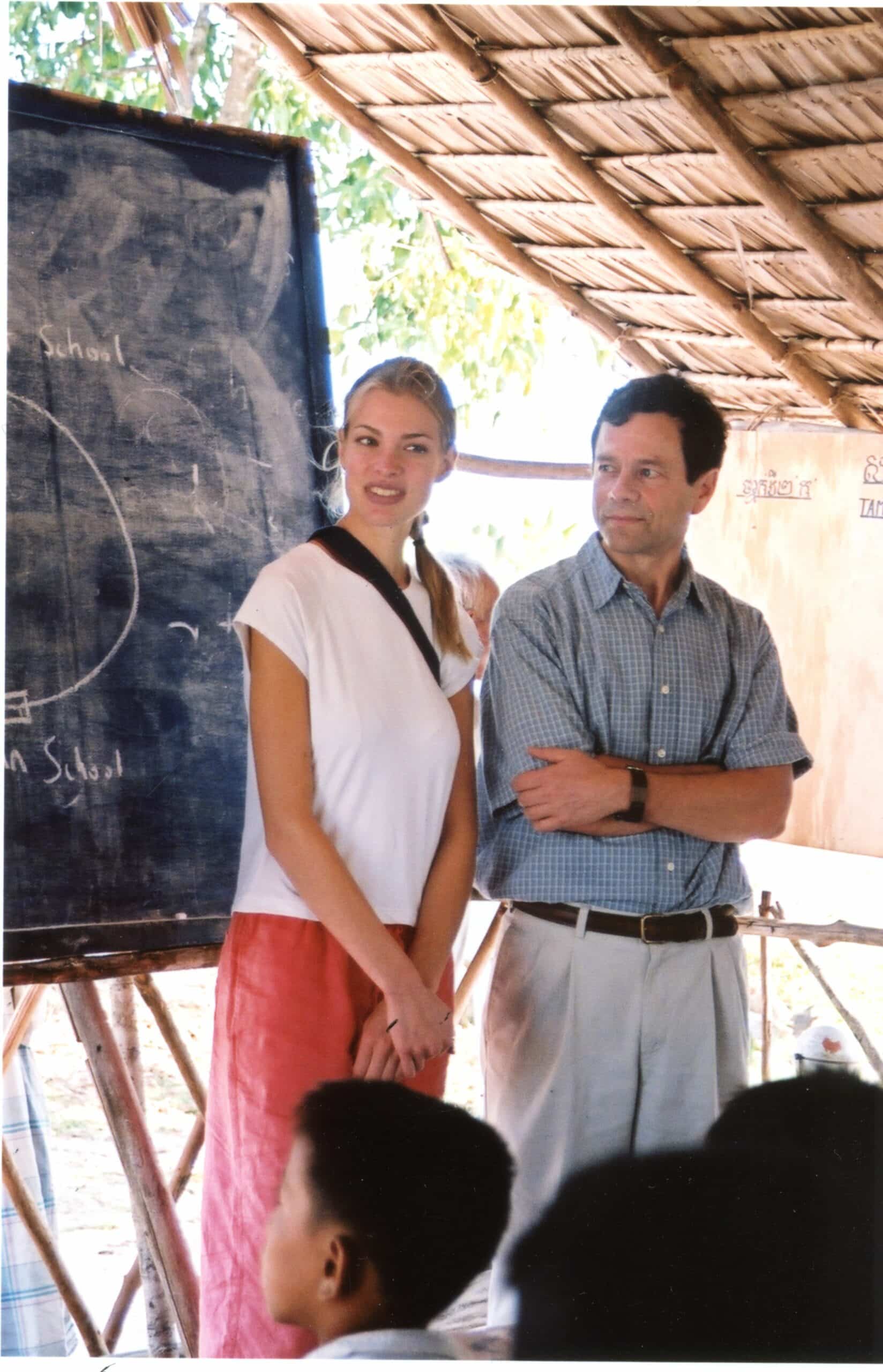

I had come to this remote village with my twenty-three-year-old daughter Elyse at the encouragement of a Unitarian minister named Fred Lipp. My daughter and I were overwhelmed by the resilience and hope of these women. Living in one-room huts with no electricity or plumbing, owning only the clothes on their backs and a few plows to tend their farms, still devastated by the destruction of the Khmer Rouge genocide of the 1970s, these women believed in the power of education.

I have learned that some opportunities present themselves only once. I went back to the United States and raised the money for a real school in Tramung Chrum. That was the beginning of Harpswell.

The next year, while hiring a man to build the school in Tramung Chrum, I met a Cambodian woman named Veasna Chea. Veasna’s story changed my life. As for so many Cambodians, her father and brother had been killed by the Khmer Rouge. Despite this tragedy, Veasna excelled in school and was totally focused on getting a university education. However, she faced severe obstacles, chief among them the lack of housing for female university students.

Until very recently, universities in Cambodia did not provide dormitories for their students. Most universities are located in Phnom Penh, the capital city, but 80% of the population lives in the countryside. Housing is not difficult for male students, who can live in the Buddhist temples or safely rent rooms together, but those options are not open to female students. So, Veasna and half a dozen other students lived underneath the university building, in the six-foot crawl space between the bottom of the building and the mud. Snakes sometimes visited during the seasonal floods. And this brave group of students lived in that horror of a space for four years.

When I heard Veasna’s story, I realized that she was more courageous than I had ever been. And I was impressed by her belief in the power of education, like the women of Tramung Chrum. Together, Veasna and I came up with the idea of building a dormitory for female students attending university in Phnom Penh. Again, I went back to the US and raised the money. The facility was finished in 2006 and was the first of its kind in Cambodia.

Having the only such facility in the country, we could attract the brightest young university women. And with such a valuable human resource, I decided to give these students more than free room and board. Over the following years, with the help of others, I developed an in-house academic program (which our students take in the weekends and evenings when they are not attending their regular university classes) that includes instruction in critical thinking and leadership skills, English classes, computer training, and more.

In early 2010, we completed our second facility in Cambodia, on the other side of the city. Together, the two dorms house about 80 students. As of early 2022, we have approximately 230 graduates, working as teachers, lawyers, engineers, journalists, doctors, businesswomen, directors of NGOs, and more. These women stay closely connected to each other and to Harpswell, inspiring and supporting each other as they make affirmative choices in their careers and families and lift their communities in the process.

One of those graduates, featured in the last segment of part 2 of SEARCHING, is Sothearath Sok, Class of 2018. After majoring in agriculture at the Royal University of Agriculture, she started a business called Junlen (“worm” in Khmer) to use the droppings of earth worms as fertilizer for farmers. Sothearath cultivates the worms on a farm and has sent the worms and their byproducts to over a thousand farms in Cambodia.

In 2017, Harpswell expanded its work by starting a twelve-day annual program in leadership training and critical thinking for young women from all ten countries of Southeast Asia. That program is based in Penang, Malaysia and now has about 75 graduates. Some have started their own humanitarian projects, based on what they have learned from us. Harpswell’s family continues to grow, and I hope that the passion for education and desire to improve their communities and world continues into future generations.

The Big Bang

Every civilization has had its story of how the universe began. One of the oldest preserved stories of Creation, much older than Genesis in the Hebrew Bible, is the Babylonian Enuma Elish (“The World Above”), dating to sometime before the fall of the Sumerian empire in 1750BC. The first tablet begins at the beginning:

When a sky above had not yet even been mentioned

And the name of firm ground below had not yet even been thought of;

When only primeval Apsu, their begetter,

And Mummu and Ti’amat – she who gave birth to them all –

Were mingling their waters in one;

When no bog had formed and no island could be found;

When no god whosoever had appeared,

Had been named by name, had been determined as to his lot,

Then were gods formed within them.

Some of the first gods formed were Anu, the god of the sky, Nudimmut, the god of water, and Enlil, the god of wind and earth. Thus, the ancient Babylonians viewed the universe as made of these fundamental elements. However, the divinities seethed in disorganized chaos inside the body of Ti’amat. At some point, the hero of the story is born, Marduk, a god of storm and thunder. Marduk does battle with Ti’amat and her army. When he triumphs, Marduk crushes her skull, drains her arteries, and with his axe cuts her body in two. Half of the body he lifts up to form the sky, the other half remains to form the water and earth. In this way, Marduk has brought order to the world.

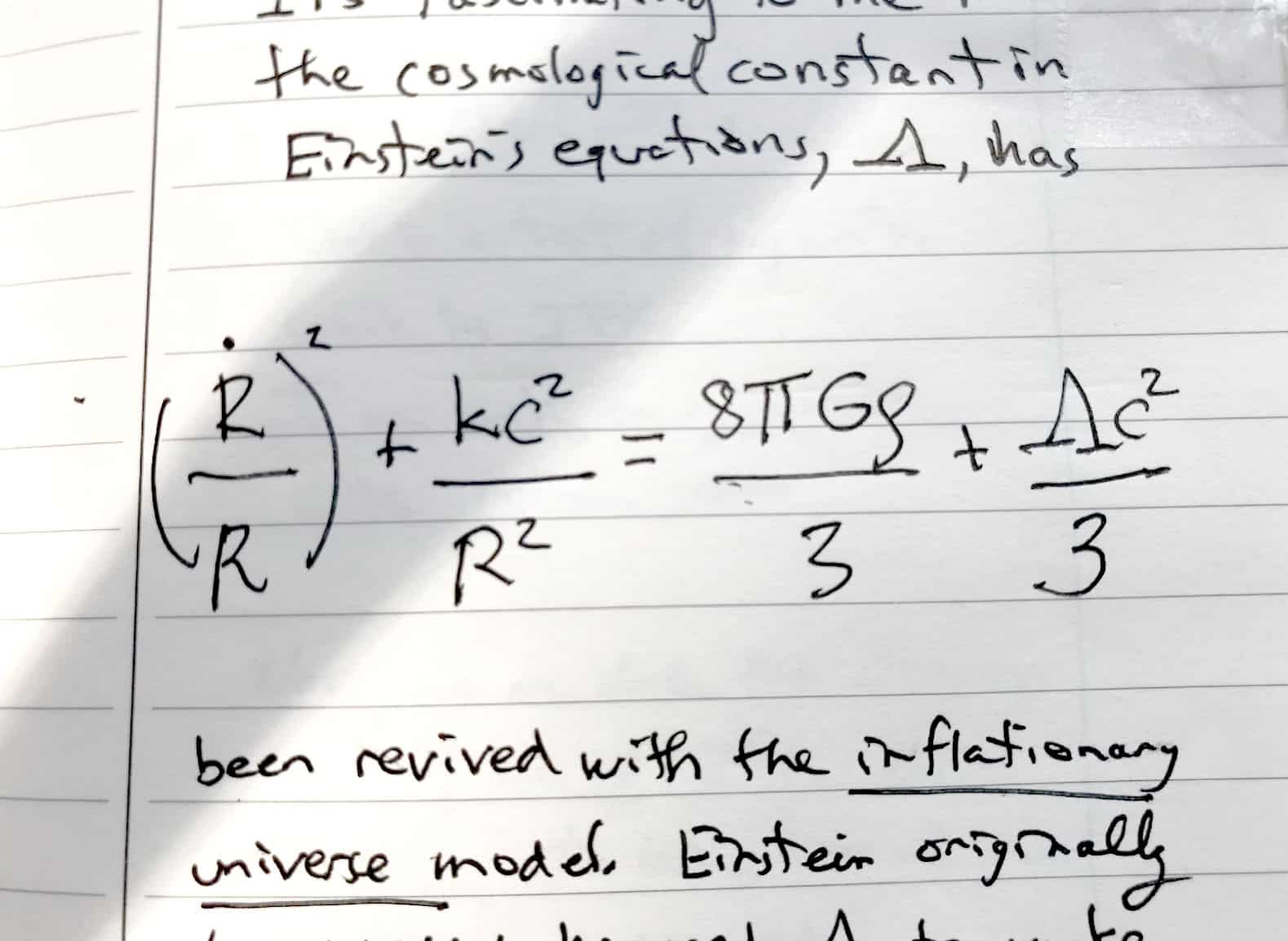

Many thinkers, from ancient times to modern, have assumed that the universe has existed forever, with no beginning. For example, Aristotle supported that view and gave philosophical arguments for why it must be so. In 1917, when Einstein first applied his new theory of gravity to the universe as a whole, he assumed that the universe was static and even modified his equations to guarantee that fact.

In 1922, a Russian physicist named Alexander Friedmann found solutions to Einstein’s cosmological equations for a universe evolving in time. However, Friedmann’s work went unnoticed. Furthermore, there are different solutions to Einstein’s equations, some with static cosmologies and some with evolving cosmologies.

Then, in 1927, a prominent Belgian scientist, Georges Lemaitre, suggested that the recently observed “redshifts” of galaxies might be interpreted as an expanding universe, like an expanding balloon. (When luminous objects are moving, their light changes color, just as the pitch of a moving train changes. The colors of objects moving away from you shift to the red, hence the name “redshift.” Colors of objects moving toward you shift towards the blue. The greater the speed, the greater the shift of colors.) Einstein, still wedded to the idea of a static universe, pronounced Friedmann’s and Lemaitre’s ideas “abominable.” [See Georges Lemaitre’s memories of talking to Einstein at the 1927 Solvay conference, “Rencontres avec A. Einstein,” Revue des Questions Scientifiques 129 (1958)]

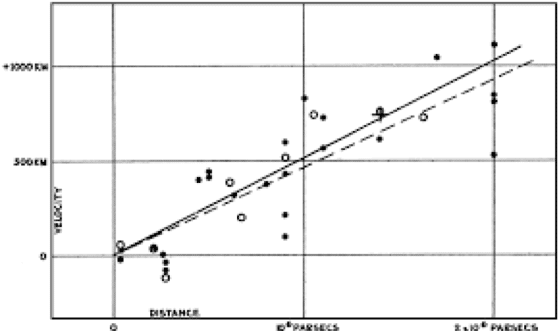

The tide turned in 1929. In that year, American astronomer Edwin Hubble, using the l00-inch Hooker telescope at Mount Wilson, near Los Angeles, California, observed that the speed at which galaxies were moving away from us was proportional to their distance. On the right is his original diagram, where the vertical axis is the speed and the horizontal axis is the distance away.

In other words, a galaxy twice as far away as a closer galaxy is moving away from us at twice the speed of the nearer galaxy. The speeds were determined by measuring the redshifts of the galaxies. Their distances were determined by a new method involving pulsating stars, developed by the underappreciated American astronomer Henrietta Leavitt.

The interpretation of Hubble’s “speed-proportional-distance” finding is that the universe is expanding, with space literally stretching. You can demonstrate this yourself by putting marks on a rubber band one inch apart (each mark representing a galaxy). Now hold any one of the marks at the 0 mark of a ruler and began stretching the rubber band. You will find that the mark initially at the one inch mark moves to two inches in the same time that the mark initially at the two inch mark moves to four inches. It has moved twice as far in the same period of time, thus it is moving twice as fast. In other words, in a uniformly expanding material, speed is proportional to distance, just as Hubble found with the galaxies.

After Hubble’s discovery, Einstein threw in the towel and acknowledged that the universe is expanding. Furthermore, the rate of expansion can be measured. If we imagine reversing time, the galaxies move closer and closer together until, at a definite moment in the past, calculated by the rate of expansion today, all the material of the universe was crammed together in a point. That definite moment in the past has been measured to be about 13.7 billion years ago and is called the Big Bang.

Physicists went back to Friedmann’s equations for an evolving universe and used them to calculate the properties of the universe from the Big Bang up until now, including such things as the density of matter and energy, and the temperature of the universe at each moment of time. Today, almost all scientists accept the Big Bang model of the universe. The model has been confirmed by various other observations, including the ubiquitous cosmic radio waves, and the ratio of hydrogen to helium in stars, elements formed during the first few seconds after the Big Bang and predicted by that model.

We still do not have a good theory for how the Big Bang happened. However, we believe that some kind of time and space probably existed before the Big Bang, with universes constantly coming into being due to the interplay between quantum physics and gravity. A theory that combines Einstein’s theory of gravity, called General Relativity, with quantum physics is called “quantum gravity.” Physicists are now hard at work on that theory. (See article on Planck scale)

The Planck Scale

One way of looking at the history of physics is through the lens of the search for smaller and smaller fundamental elements of matter. Although the ancient Greeks hypothesized the existence of a tiny, indestructible smallest element called the atom, the size of atoms was not measured until the mid-nineteenth century, when the Austrian physicist Johann Josef Loschmidt used the theory of molecules in motion and measurements of gases. In 1905, Einstein gave a more accurate estimate, using the observed motion of particles suspended in a liquid, called “Brownian motion.” In 1897, the British physicist J.J. Thomson observed electrically charged particles called electrons, much smaller than atoms. And in 1911, the New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford and colleagues found evidence for the nucleus of the atom, containing 99.9% of the atom’s mass and concentrated in a region 100,000 times smaller than the atom as a whole. At this point, it was clear that there were particles much smaller than atoms.

In the 1950s and 1960s, using the new machines called particle accelerators, also called “atom smashers” (see my “read more” article on CERN, which could probe matter at scales much smaller than atoms, a whole zoo of new subatomic particles were discovered. Those early particle accelerators were followed by more advanced machines, like Fermilab, SLAC, and CERN, with even more energy for hurling subatomic particles at each other. It was found, for example, that the protons and neutrons at the centers of atoms are each made of three even smaller and more fundamental particles called quarks.

Naturally, physicists began asking whether the process of breaking matter into smaller and smaller pieces could continue indefinitely. The answer is no. At an extremely tiny scale, one trillionth of one trillion the size of an atom, or about 10-33 centimeters, gravity and quantum physics join together to introduce a fluctuating graininess to space itself. Gravitational physics tells us that matter and energy bend time and space. Quantum physics tells us that at very tiny sizes, matter acts as if it were spread out in a diffuse fog. At this ultra-tiny size, called the Planck scale after the German physicist Max Planck (1858 -1947), a pioneer in quantum physics, we can picture space as a seething caldron of bubbles, appearing and disappearing, each bubble the size of a Planck diameter. The smooth nature of space that we and our machines experience is a result of averaging out the rapid fluctuations of space at the Planck scale, just as an ocean punctuated with rapidly forming and dissolving ripples looks smooth and calm when viewed from a thousand feet up. We cannot probe nature at a size smaller than the Planck scale, because space itself has no existence smaller than this scale.

To understand in detail the nature of space and time at the Planck scale, we would need a theory of quantum gravity, which we do not yet possess. However, we can estimate the size of the Planck scale, where quantum physics, gravity, and relativity all play a role. Gravitational physics is regulated by the size of Newton’s gravitational constant, G= 6.67 x 10-8 cm3 g-1 s-2 . Quantum physics is regulated by Planck’s constant, h = 6.63 x 10-27 cm2 g s. And relativity is regulated by the speed of light, c = 3 x 1010 cm s-1 . All of these fundamental constants of nature must appear in determining the Planck scale, and there is only one combination of them that has units of length: (hG/c3)1/2 , which is approximately equal to 10-33 centimeters.

In probing nature at smaller and smaller scales, the Planck length is the end of the line. At the Planck length and smaller, space itself loses its meaning, like a sweater at scales smaller than the width of individual threads.

Galileo

Galileo was born in Pisa and grew up in Florence. After 1592, he taught mathematics at the University of Padua. Unable to discharge his financial responsibilities on his academic salary alone – he had to pay the dowries of his sisters in addition to supporting his three children by a mistress – he took in boarders and sold scientific instruments. In the late 1580s, he performed his famous experiments with motion and falling bodies. In 1609, at the age of forty-five, he heard about a new magnifying device just invented in the Netherlands. Without ever seeing that marvel, he quickly designed and built a telescope himself, several times more powerful than the Dutch model. He seems to have been one of the very first human beings to point such a thing at the night sky. (The telescopes in Holland were called “spyglasses,” leading one to speculate on their uses.)

Grinding and polishing his own lenses, Galileo’s first instruments magnified objects a dozen or so times. He was eventually able to build telescopes that made objects appear 30 times closer than they actually were, and magnified a thousand times. You can see Galileo’s surviving telescopes in the Museo Galileo, in Florence, as seen in Part 1 of SEARCHING. His first telescope was 36.5 inches long and 1.5 inches wide, a tube made of wood and leather with a convex lens at one end and a concave eyepiece on the other. The field of view of this early telescope is extremely small, appearing as a dime-sized circle of light at arm’s length at the end of a long tube. And dim. (See this animation showing the field of view.)

It’s hard to imagine the thrill and surprise Galileo must have felt when he first looked up with his new instrument and gazed upon the “heavenly bodies” – described for centuries as the revolving spheres of the Moon, Sun, and planets. Beyond were the revolving crystalline spheres holding the stars, and finally the outermost sphere, the Primum Mobile, spun by the finger of God. All of it supposedly constructed out of aether, Aristotle’s fifth element, unblemished and perfect in substance and form. And all of it at one with the divine sensorium of God. What Galileo actually saw through his little tube were craters on the moon and dark acne on the sun.

In his little book The Starry Messenger (Sidereus Nuncius in its original Latin), hastily written and published in 1610, Galileo reports what he saw after turning his new telescope towards the heavens. He exhibits his own pen and ink drawings of the Moon seen through his telescope, showing dark and light areas, valleys and hills, craters, ridges, mountains. He even estimates the height of the lunar mountains by the length of their shadows. Later, he observed spots on the Sun. All of this was strong evidence that the heavenly bodies are made of ordinary material, like farm fields and oceans on Earth. The result caused a revolution in thinking about the separation between Heaven and Earth, a mind-bending expansion of the territory of the material world. The materiality of the stars, combined with the law of the conservation of energy, decrees that the stars are doomed to extinction. The stars in the sky, the most striking icons of immortality and permanence, will one day expire and die. Everything in the cosmos passes away.

Alan Lightman is unique as the first professor at MIT to hold faculty positions in both the sciences and humanities. But he is also unusual in spending a considerable amount of time and effort as a social entrepreneur, outside of his contributions as an academic and a best-selling author. As you can read here, and see in this video, his work with Harpswell in Cambodia and across Southeast Asia has been a powerful contributor to the education and empowerment of a large number of female students who would otherwise have had nowhere to live during their university studies.